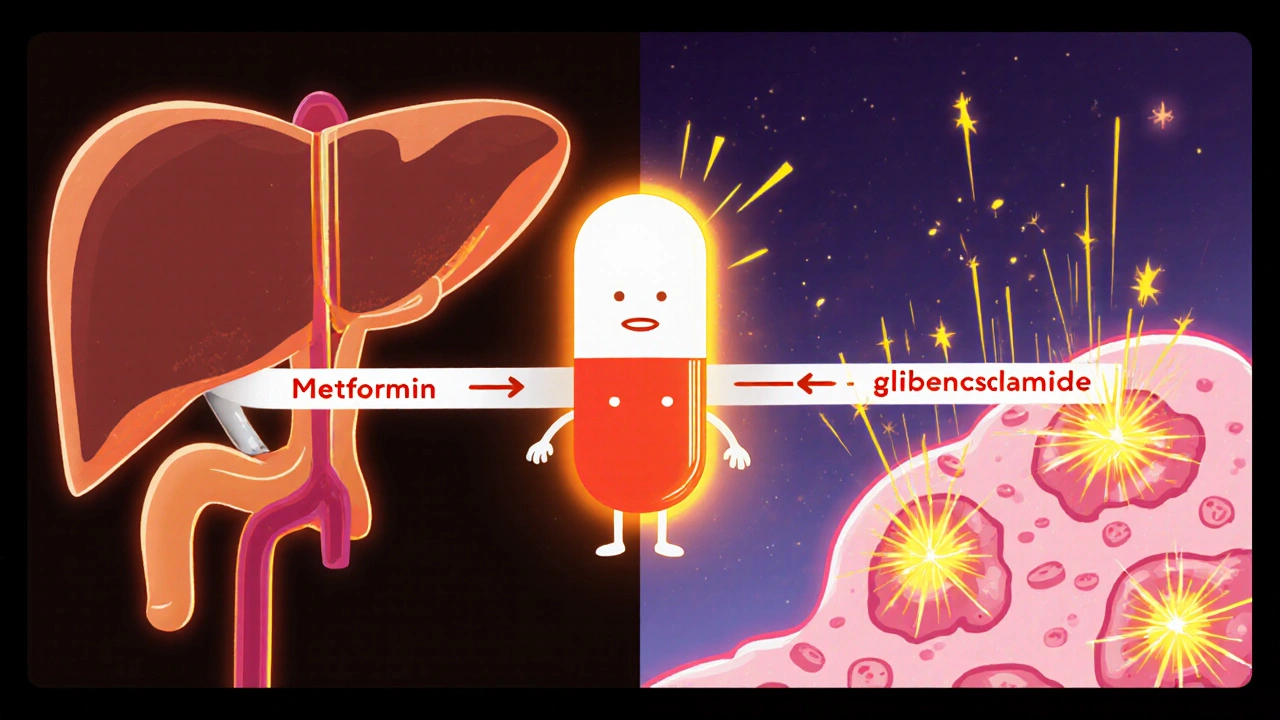

When managing type 2 diabetes, Glucovance is a fixed‑dose combination of metformin and glibenclamide. It aims to simplify therapy by merging a biguanide with a sulfonylurea in one pill.

Key Takeaways

- Glucovance combines two well‑known agents, offering convenience but also inheriting side‑effects from both.

- Biguanides (metformin) lower glucose mainly by reducing liver output, while sulfonylureas (glibenclamide) stimulate insulin release.

- Alternatives such as Janumet, metformin‑only, or newer SGLT2 inhibitors often provide better weight control and lower hypoglycemia risk.

- Cost varies widely; generics of the individual components are usually cheaper than the fixed‑dose combo.

- Choosing the right regimen hinges on patient‑specific factors: kidney function, risk of low blood sugar, and personal preference for pill burden.

How Glucovance Works

Metformin belongs to the biguanide class. It suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, improves peripheral insulin sensitivity, and modestly reduces appetite. Glibenclamide, a sulfonylurea, binds to the SUR1 subunit of the ATP‑sensitive potassium channel in pancreatic β‑cells, prompting insulin secretion. By delivering both mechanisms together, Glucovance can achieve a roughly 1.5‑2 % greater HbA1c drop than metformin alone, especially in patients whose pancreas still produces insulin.

However, the sulfonylurea component also brings a higher chance of hypoglycemia, particularly in the elderly or those with irregular meals. Metformin’s most common adverse effect is gastrointestinal upset, which can be mitigated by using the extended‑release form.

Key Comparison Criteria

Before diving into the table, decide which factors matter most for you or your patients:

- Mechanism of action: Does the drug target liver output, insulin secretion, or renal glucose re‑absorption?

- HbA1c reduction: Typical clinical trial data on average percent points lowered.

- Weight impact: Some agents cause weight gain (sulfonylureas), others promote modest loss (metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors).

- Hypoglycemia risk: Critical for patients on insulin or with erratic eating patterns.

- Kidney safety: Metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors have dosing limits based on eGFR.

- Cost: Out‑of‑pocket expense can drive adherence.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Drug | Class | Typical Dose | HbA1c ↓ (points) | Common Side Effects | Approx. Monthly Cost (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucovance | Biguanide + Sulfonylurea | 500 mg/5 mg - 1000 mg/10 mg | 1.5-2.0 | GI upset, hypoglycemia | $75 |

| Metformin (generic) | Biguanide | 500 mg - 2000 mg daily | 1.0-1.5 | Diarrhea, nausea | $15 |

| Glibenclamide (generic) | Sulfonylurea | 2.5 mg - 10 mg daily | 1.0-1.3 | Weight gain, hypoglycemia | $12 |

| Janumet (metformin + sitagliptin) | Biguanide + DPP‑4 inhibitor | 500 mg/50 mg - 1000 mg/100 mg | 1.4-1.8 | Minor GI, low hypoglycemia | $180 |

| Empagliflozin | SGLT2 inhibitor | 10 mg - 25 mg daily | 0.5-0.8 | UTI, genital mycotic infection | $150 |

Deep Dive into Popular Alternatives

Metformin‑only therapy remains the first‑line recommendation for most patients. It’s cheap, weight neutral, and has cardiovascular benefit. The major drawback is GI intolerance, which can be eased by a slow‑up titration or using the extended‑release formulation.

Glibenclamide alone is rarely started today because newer sulfonylureas (e.g., glimepiride) have a slightly lower hypoglycemia profile. It’s useful when cost is the primary concern and the patient has good renal function.

Janumet pairs metformin with sitagliptin, a DPP‑4 inhibitor that increases incretin levels. This combo provides stronger glucose control without the weight gain of sulfonylureas, and hypoglycemia is uncommon unless combined with insulin.

Empagliflozin (and other SGLT2 inhibitors) works by blocking glucose re‑absorption in the kidney. Besides modest HbA1c reduction, it lowers blood pressure, promotes weight loss, and reduces heart‑failure hospitalizations. Risks include dehydration and genital infections.

Newer agents like tirzepatide (a dual GIP/GLP‑1 receptor agonist) offer even larger HbA1c drops (up to 2.5 %) and significant weight loss, but they are injectable and pricier.

Pros and Cons of Glucovance

- Pros

- Convenient single‑pill regimen.

- Combines two complementary mechanisms.

- Effective for patients who need both metformin and a sulfonylurea.

- Cons

- Fixed ratio limits dose flexibility; you can’t adjust metformin without also changing glibenclamide.

- Higher hypoglycemia risk compared to metformin alone or DPP‑4 combos.

- Costly vs. generic separate pills.

- GI side effects persist from metformin.

When to Choose Glucovance

Consider Glucovance if a patient:

- Has already tolerated both metformin and glibenclamide separately.

- Prefers reducing pill count for adherence.

- Does not have high hypoglycemia risk (e.g., no erratic meals, no advanced age).

- Has adequate renal function (eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m²) to safely use metformin.

If any of these conditions are not met, a more tailored regimen-such as metformin + a DPP‑4 inhibitor or an SGLT2 inhibitor-might be safer and more cost‑effective.

Practical Tips for Switching

- Assess current doses of metformin and glibenclamide; match them to the closest Glucovance strengths.

- Educate patients about recognizing hypoglycemia symptoms and when to eat.

- Start with the lowest available strength (e.g., 500 mg/5 mg) if the previous regimen used lower doses.

- Monitor fasting glucose and HbA1c at 4‑ and 12‑week intervals.

- If GI upset persists, consider switching to metformin‑ER and adding a different sulfonylurea or DPP‑4 inhibitor.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main advantage of Glucovance over taking metformin and glibenclamide separately?

The biggest benefit is convenience: one pill replaces two, which can improve adherence, especially for patients who struggle with multiple daily doses.

Does Glucovance cause more weight gain than metformin alone?

Yes, because the sulfonylurea component tends to promote weight gain, offsetting metformin’s neutral effect. Patients often see a modest 1-2 kg increase over several months.

Is Glucovance safe for people with kidney disease?

Metformin is contraindicated when eGFR falls below 30 mL/min/1.73 m², and sulfonylureas accumulate in severe renal impairment, raising hypoglycemia risk. In such cases, doctors usually avoid Glucovance.

How does the cost of Glucovance compare with generic separate pills?

A month’s supply of Glucovance averages $70‑$80, whereas buying generic metformin and glibenclamide separately typically costs under $30. Insurance coverage can narrow the gap, though.

Can I take Glucovance with an SGLT2 inhibitor?

Yes, many clinicians combine a basal sulfonylurea‑biguanide combo with an SGLT2 inhibitor for added glucose lowering, provided kidney function is adequate and hypoglycemia is monitored.

In the end, the decision comes down to balancing efficacy, safety, cost, and personal preference. Glucovance can be a handy tool for the right patient, but newer agents often provide a smoother safety profile. Talk with a healthcare professional to weigh the numbers against your lifestyle.

Comments

kevin burton

Glucovance offers a convenient way to combine metformin and glibenclamide, which can simplify dosing for patients who are already stable on both agents. The combo typically lowers HbA1c by about 1.5‑2 % compared with metformin alone. However, the sulfonylurea part still carries a risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults. Cost is higher than separate generics, so insurance coverage becomes a key factor. Overall, it makes sense for patients who need both drugs and prefer fewer pills.

Olivia Harrison

It’s helpful to remember that patient preference often drives the decision more than just the numbers. If someone struggles with remembering multiple doses, a single‑pill option can improve adherence. At the same time, clinicians should monitor for low blood sugar and gastrointestinal upset after the switch. Open communication about side‑effects can prevent unnecessary discontinuation.

Veronica Appleton

I totally get that some people cant keep up with multiple pills its a real hassle especially when they have busy lives and the first pill is already enough sometimes

Terell Moore

Ah, the allure of a “one‑pill wonder”-how delightfully simplistic. One would think that compressing two pharmacologic actions into a single tablet solves every adherence issue, yet the reality is far more nuanced. The sulfonylurea component stubbornly clings to its propensity for hypoglycemia, a reminder that convenience does not equal safety. Moreover, the fixed dose ratios strip clinicians of the ability to titrate each component independently, which can be vexing for nuanced glycemic control. And let us not overlook the price premium that brand‑name combos command over their humble generics. In short, the pill is tidy, but the therapeutic trade‑offs remain messy.

Tamara Tioran-Harrison

Indeed, nothing says “patient‑centred care” like a price‑gouged tablet that still forces you to gamble with hypoglycaemia. One must applaud the pharmaceutical industry’s ingenuity in packaging risk with convenience :)

Nathan Comstock

Let us not be fooled by the glossy marketing brochures that parade Glucovance as the panacea for all type‑2 diabetes sufferers. The reality, dear readers, is that this combination pill is but a compromise-an uneasy marriage of metformin’s hepatic restraint and glibenclamide’s insulin‑stimulating bravado. The former, a stalwart of first‑line therapy, offers modest weight neutrality and cardiovascular protection, while the latter, a sulfonylurea, delights in coaxing the pancreas to secrete insulin at the peril of hypoglycaemia. When pressed together in a single tablet, their synergistic potential may achieve an HbA1c reduction of up to two percent, yet this modest gain is shadowed by a heightened risk of low blood sugar, especially in the elderly or those with erratic eating patterns. Moreover, the fixed‑dose nature shackles the prescriber, denying the flexibility to titrate metformin upward while keeping the sulfonylurea modest-a limitation that can thwart optimal glycaemic fine‑tuning. The gastrointestinal distress inherent to metformin, though often mitigated by extended‑release formulations, persists, and the sulfonylurea’s propensity for weight gain merely counteracts metformin’s neutral stance. Financially, the combo sits at a premium, often eclipsing the sum of its generic constituents, thereby imposing an additional burden on patients already navigating the labyrinth of healthcare costs. While certain patients-those already stable on both agents and yearning for pill‑count reduction-may derive genuine benefit, the broader diabetic population would be wiser to consider newer classes such as SGLT2 inhibitors or DPP‑4 inhibitors, which offer weight loss, lower hypoglycemia risk, and ancillary cardiovascular advantages. Clinicians must also weigh renal function, as metformin’s safety threshold and sulfonylurea accumulation become problematic in declining eGFR. Monitoring should be intensified during the initial weeks of therapy, with attention to fasting glucose trends and any episodes of dizziness or sweating. Education on recognizing hypoglycemia symptoms becomes paramount, particularly for patients with irregular meal schedules. Some practitioners opt to initiate the two agents separately before contemplating a fixed‑dose, preserving titration freedom. In the grand tapestry of diabetes management, Glucovance is a thread that holds together but does not shine; it belongs in a niche, not as a universal solution. Future formulations may address dosage flexibility, but until then, prescribers must balance convenience against the inevitable trade‑offs. Therefore, shared decision‑making remains the cornerstone when selecting Glucovance.

Jennifer Stubbs

While the dramatic prose paints a vivid picture, the data remain clear: Glucovance offers modest HbA1c improvement at the cost of higher hypoglycemia risk. In patients with stable renal function and predictable meals, the convenience factor can indeed outweigh these drawbacks. However, the fixed‑dose ratio frequently forces clinicians to compromise on metformin titration, which may limit maximal glycemic control. Cost considerations also tip the balance, as generics of the individual components are substantially cheaper. Ultimately, the decision should be individualized, weighing adherence benefits against safety and financial burden.

Abby W

Exactly! 😊 The trade‑off between pill‑burden and side‑effects is a classic dilemma. Adding a smiley can’t fix hypoglycemia, but it does remind us to keep the conversation light. 🐱👓 Just make sure patients know the signs of low blood sugar, even if they’re happy with the convenience. 👍

Sarah Keller

The philosophical underpinnings of drug choice often get lost in the number‑crunching, yet we must confront the ethical dimension of prescribing a medication that deliberately trades safety for simplicity. When a patient’s well‑being is at stake, convenience should never be the sole arbiter. A rigorous risk‑benefit analysis, paired with transparent patient dialogue, is the only responsible path forward. In short, the allure of “one‑pill” should not blind us to its inherent compromises.

the sagar

Glucovance is just a marketing gimmick.

Abhinav B.

i think u r overreacting its not all bad its just a combo pill but u should read the label first

Clinton Papenfus

While the sentiment expressed reflects a colloquial perspective, a more measured appraisal is warranted. The pharmacological synergy of metformin and glibenclamide does confer certain therapeutic advantages, yet the attendant risks of hypoglycemia and gastrointestinal intolerance must be judiciously evaluated. Moreover, the economic implications of a fixed‑dose formulation merit consideration, particularly in health systems burdened by cost constraints. It is incumbent upon the prescriber to engage in a thorough discussion with the patient, outlining both benefits and potential adverse outcomes, thereby facilitating an informed consent process.

Grace Silver

Indeed, the dialogue we are having underscores the broader philosophical question of how we balance convenience with patient autonomy. When we reduce complex regimens to a single tablet, we risk oversimplifying the lived experience of managing chronic disease. Yet, for many individuals, that very simplification can be a gateway to better adherence and improved outcomes. The ethical responsibility lies in presenting all facets-clinical efficacy, safety profile, and financial cost-without bias, empowering the patient to make a decision aligned with their values. In this way, the conversation moves beyond mere pharmacology into the realm of shared humanity.