Cancer-Related Pulmonary Embolism Risk Calculator

When a person is diagnosed with Pulmonary Embolism is a blockage in a lung artery caused by a blood clot that has traveled from elsewhere in the body, the news can feel like a double blow. Add cancer to the mix, and the risk of that clot forming spikes dramatically. This article breaks down why cancer patients are far more prone to PE, what mechanisms drive the connection, and how doctors and patients can spot and manage the danger early.

Why Cancer Makes Blood Clots More Likely

At its core, cancer creates a hyper‑coagulable state-meaning the blood is primed to clot. Several factors contribute:

- Tumor‑derived tissue factor: Many tumors release tissue factor, a protein that kick‑starts the clotting cascade.

- Inflammation: Cytokines such as IL‑6 increase platelet activation.

- Compression of veins: Large abdominal tumors can press on pelvic veins, slowing blood flow.

- Immobility: Hospital stays, surgery, and fatigue keep patients in bed longer.

- Treatment‑related effects: Chemotherapy and radiation can damage vessel walls and alter clotting factors.

All of these fall under the umbrella term hypercoagulability, a hallmark of what clinicians call cancer‑associated thrombosis.

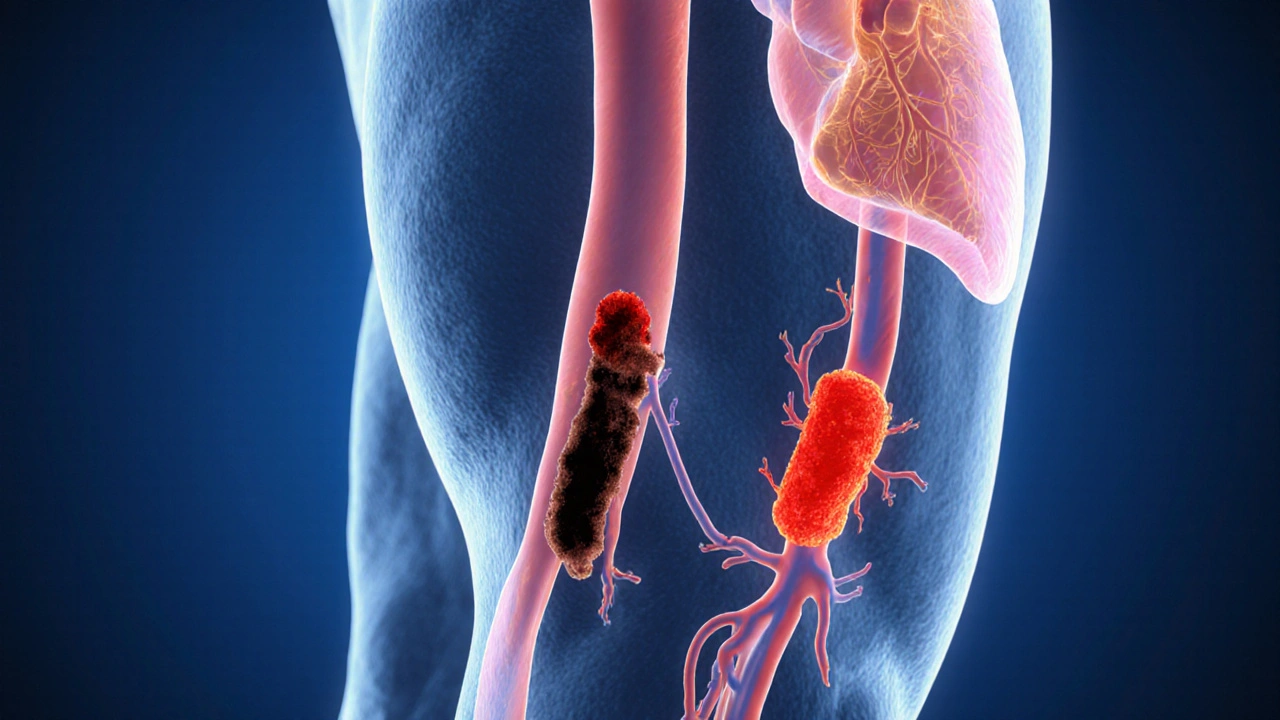

From Deep Vein Thrombosis to Pulmonary Embolism

Most PEs start as a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the legs or pelvis. When a clot breaks loose, it travels through the venous system, reaches the right heart, and is pumped into the lungs. This cascade is known as venous thromboembolism (VTE), the broader category that includes both DVT and PE.

In cancer patients, the incidence of VTE can be as high as 20% in the first six months after diagnosis, compared with less than 1% in the general population.

Incidence of Pulmonary Embolism by Cancer Type

| Cancer Type | PE Incidence | Key Risk Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic | 44 | High tissue factor expression |

| Lung | 34 | Direct vascular invasion |

| Gastric | 27 | Chemotherapy‑induced endothelial damage |

| Breast | 12 | Hormonal therapy |

| Prostate | 9 | Androgen deprivation therapy |

These numbers come from large registry studies up to 2024 and highlight that not all cancers carry the same risk. Pancreatic and lung cancers top the list, so clinicians keep a closer eye on those patients.

Clinical Signs That Should Raise Alarm

PE can be silent, but when symptoms appear they often mimic other illnesses, making diagnosis tricky. In a cancer setting, watch for:

- Sudden shortness of breath that worsens at rest.

- Sharp chest pain that intensifies with deep breathing.

- Rapid heart rate (tachycardia) without fever.

- Unexplained drop in blood oxygen saturation.

- Swelling or pain in a leg-possible DVT precursor.

Because cancer patients may already experience fatigue or dyspnoea from tumour burden, clinicians often rely on biomarkers like D‑dimer and imaging (CT pulmonary angiography) to confirm PE.

Managing the Double Threat: Anticoagulation Strategies

Once PE is confirmed, the mainstay of treatment is anticoagulation. However, cancer patients pose a dilemma: they need strong clot prevention but also have higher bleeding risks, especially after surgery or during thrombocytopenia from chemotherapy.

Current guidelines recommend low‑molecular‑weight heparin (LMWH) as first‑line, but direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) like apixaban are gaining traction for their oral convenience. The choice hinges on:

- Kidney function (creatinine clearance).

- Drug‑drug interactions with chemotherapy agents.

- Platelet count (keep >50×10⁹/L when possible).

- Location of tumour (gastrointestinal tumours have higher bleeding risk with DOACs).

In high‑risk scenarios, temporary placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter may be considered, but filters carry their own complications and are not a long‑term solution.

Prevention: Reducing the Chance of PE Before It Happens

Prevention strategies are layered:

- Risk assessment tools such as the Khorana score help identify patients who need prophylactic anticoagulation.

- Mechanical methods like graduated compression stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression for bedridden patients.

- Pharmacologic prophylaxis - low‑dose LMWH or low‑dose DOACs during high‑risk periods (e.g., after major surgery).

- Lifestyle tweaks - encouraging ambulation, hydration, and smoking cessation.

Studies published through 2023 show that appropriate prophylaxis can cut VTE rates by up to 50% in high‑risk cancer cohorts.

Key Take‑aways for Patients and Caregivers

- Know that cancer itself makes blood more clot‑prone - it’s not just the treatment.

- If you experience sudden breathlessness or chest pain, seek medical help right away.

- Ask your oncologist about a VTE risk assessment; a simple questionnaire could change your medication plan.

- Follow any prescribed anticoagulation regimen exactly; missing doses can be as dangerous as bleeding.

- Stay active, stay hydrated, and keep track of any leg swelling.

Understanding the link between cancer and pulmonary embolism empowers you to catch warning signs early and work with your care team on a safe prevention plan.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does cancer increase the risk of blood clots?

Tumours release proteins like tissue factor, trigger inflammation, and can compress veins. Combined with immobility and chemotherapy‑induced vessel damage, these factors create a hypercoagulable environment that makes clots more likely.

What symptoms should a cancer patient watch for that could signal a PE?

Sudden shortness of breath, sharp chest pain that worsens with breathing, rapid heartbeat, unexplained low oxygen levels, and swelling or pain in a leg are the most common red flags.

Is anticoagulation safe for patients undergoing chemotherapy?

Generally yes, but dosage and drug choice must consider kidney function, platelet counts, and interactions with chemotherapeutic agents. Low‑molecular‑weight heparin is often preferred, though DOACs are an option for many patients.

How does the Khorana score help prevent PE?

The Khorana score assigns points based on cancer type, blood counts, and body mass index. A score of 2 or higher flags patients who benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation, reducing their VTE risk.

Can lifestyle changes lower the risk of PE in cancer patients?

Yes. Regular ambulation, adequate hydration, avoiding prolonged immobility, and quitting smoking all help keep blood flowing and reduce clot formation.

Comments

Barry White Jr

Great overview keep sharing useful info

Andrea Rivarola

The article does a solid job laying out the pathophysiology behind cancer‑associated thrombosis, which is essential for both clinicians and patients to understand. It starts by explaining how tumors release tissue factor, a potent initiator of the coagulation cascade, and then moves on to the role of inflammatory cytokines like interleukin‑6. The piece also highlights the mechanical factors such as venous compression by large abdominal masses, which can impede blood flow. I appreciate the clear distinction made between deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, reinforcing that most PEs originate from leg or pelvic clots. The statistics presented are striking, especially the up to 20 % incidence of venous thromboembolism in the first six months after a cancer diagnosis. The breakdown of incidence by cancer type, with pancreatic and lung cancers at the top, really underscores the need for heightened vigilance in those populations. The discussion of clinical signs is thorough, reminding us that symptoms can mimic other conditions, which complicates diagnosis. The section on anticoagulation wisely notes the balance between clot prevention and bleeding risk, especially in the context of thrombocytopenia. I found the comparison between low‑molecular‑weight heparin and direct oral anticoagulants particularly useful, as many patients ask which is safer. The mention of IVC filters as a temporary measure adds depth, acknowledging that they are not a panacea. Prevention strategies are presented in a layered fashion, from risk assessment tools like the Khorana score to mechanical methods and lifestyle modifications. The emphasis on ambulation, hydration, and smoking cessation aligns with broader public‑health recommendations. The article also correctly points out that prophylactic anticoagulation can halve VTE rates in high‑risk cohorts, which is a compelling statistic for clinicians. The key take‑aways section neatly summarizes the most actionable points for patients and caregivers. Overall, the piece combines scientific detail with practical guidance, making it a valuable resource for anyone navigating the complexities of cancer‑related clot risk.

Tristan Francis

Everyone talks about clot risk but doesn’t mention the hidden agenda of pharma pushing expensive drugs. The data on DOACs is often funded by the manufacturers themselves. Big companies want us to believe that newer meds are always better. It’s a simple trick to keep profits high while patients bear the cost.

Keelan Walker

Wow this article really breaks it down 😃

It’s so helpful to see how each factor stacks up on the risk ladder 🚀

The emojis just make the serious stuff a bit lighter 😅

I love how you highlighted the importance of staying active 💪

Even the long‑term outlook feels hopeful when you read about prophylaxis options 🙌

Keep up the great work 🙏

Thanks for sharing such a thorough guide 🙏

It really empowers patients to ask the right questions 🗣️

And the table of cancer types is super clear 📊

Overall this is a fantastic resource for anyone dealing with cancer and clot worries 😇

Heather Wilkinson

👍 Great job Barry! This info is so useful 😊

Henry Kim

I think it’s important to remember that every patient’s situation is unique, so while the guidelines provide a solid framework, individualized assessment remains key. The balance between clot prevention and bleeding risk can be delicate, especially after surgery or during periods of low platelet counts. Engaging patients in shared decision‑making helps them understand the trade‑offs and adhere to the chosen regimen.

Neha Bharti

Understanding the interplay of biology and lifestyle offers a holistic view. It reminds us that medicine is not just about drugs but also about daily habits and choices.

Samantha Patrick

Hey Henry, great points! Just wanted to add that you can actually use a low‑dose LMWH at night – it works well for many patients. Definitely talk to your doc about timing and dosage. Also, make sure to keep an eye on any bruising – it can be a sign of bleeding.

Ryan Wilson

We should all be careful not to let patients become complacent about clot risk. It’s our duty to stress that ignoring preventive measures can lead to serious consequences. Let’s keep the conversation honest and direct.

EDDY RODRIGUEZ

Absolutely! The emotional toll of a cancer diagnosis is already massive, and adding the fear of a pulmonary embolism can feel crushing. That’s why it’s vital to have a clear prevention plan that the patient can actually follow. When you explain the why behind each step – whether it’s moving around, staying hydrated, or taking a daily anticoagulant – people feel more in control. I love seeing the way the article breaks down the options between LMWH and DOACs, because choice matters. It lets the patient feel heard and respected, especially if they have concerns about injections versus pills. And let’s not forget the power of simple encouragement: “You’ve got this, keep moving, we’ll keep an eye on the labs.” That kind of supportive language can make a huge difference in adherence and overall outlook.

Christopher Pichler

Wow, look at that – an overly optimistic pep‑talk wrapped in a sea of jargon, as if we needed more buzzwords. Sure, “empower patients” sounds nice, but let’s not forget the cost‑benefit analysis of adding another anticoagulant to a regimen already riddled with drug‑drug interactions. If you’re going to sprinkle in “patient‑centric” and “shared decision‑making,” at least back it up with real-world adherence data, not just feel‑good clichés.

VARUN ELATTUVALAPPIL

Wow!!! This post!!! Is!!! So!!! Informative!!!

April Conley

We need more data and less hype

Sophie Rabey

Great, another reminder that cancer makes everything harder – thanks for the obvious