When the first generic version of a brand-name drug hits the market, it doesn’t mean the battle is over. In fact, it’s just the beginning. The first generic gets a 180-day window of exclusive rights under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. During that time, it can charge 70-90% of the brand’s price and capture 70-80% of the market. But once that clock runs out, the floodgates open. Competitors rush in-not just one or two, but sometimes a dozen. And when they do, prices don’t just drop. They collapse.

Why the First Generic Gets a Head Start

The 180-day exclusivity period isn’t a gift. It’s a reward. The first generic company spends millions challenging patents in court, often paying $5-10 million in legal fees just to get the green light. In return, they get a temporary monopoly. That’s how they recoup the cost. During this window, they’re the only option besides the brand. Pharmacies and insurers have no choice but to buy from them. That’s why the first generic can still charge $200 a month for a drug that originally cost $300-even though the manufacturing cost is under $5. But here’s the catch: that exclusivity doesn’t protect them from the brand itself. Many brand companies launch an authorized generic-a version made by the original company but sold under a different label-on the same day the first generic enters. Merck did this with Januvia in 2019. Within six months, the authorized generic captured 32% of the market. The first generic’s share dropped from 80% to under 50%. Revenue crashed. The brand didn’t lose the market-it just shared it with its own cheaper version.What Happens When the Second Generic Arrives

The second generic doesn’t need to sue. They don’t need to prove the patent is invalid. They just copy the first generic’s bioequivalence data. That cuts their development time by 6-12 months and saves 30-40% in costs. But getting FDA approval is only half the battle. Getting into pharmacies? That’s another story. In the U.S., pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) control access. They don’t care who got approved first. They care who offers the lowest price. And they’re using a winner-take-all model: if you’re the cheapest, you get 100% of the formulary placement. So the second generic doesn’t just compete on price-they compete to be the lowest bidder. Often, they’ll undercut the first generic by 20-30% just to get on the list. That forces the first generic to slash prices too. And that’s when the real price erosion begins. By the time the third generic enters, the drug’s price has already fallen to about half of what it was at launch. The FDA found that with three generic competitors, prices drop to 49% of the brand’s original cost. With four, it’s 38%. By five or more, it’s down to 17%. That’s what happened with Crestor. In 2016, the brand sold for $320 a month. By 2017, with eight generics on the market, it was $10.Why More Competitors Don’t Always Mean Lower Prices

You’d think more companies = lower prices. But that’s not always true. In some cases, too many entrants cause chaos. A 2022 FDA report showed that 62% of generic drug shortages involved products with three or more manufacturers. Why? Because everyone is outsourcing production to the same handful of contract manufacturers. When one plant has a quality issue-say, mold in the pills or impurities in the active ingredient-all the drugs made there get pulled. Suddenly, five companies are out of stock. Patients can’t get their meds. Pharmacies panic. Prices spike again. And it’s not just manufacturing. The U.S. has 48 different state licensing rules for drug distributors. Each new generic company has to navigate them all. They also need to negotiate with group purchasing organizations (GPOs) that demand 30-40% discounts. The first generic might get 20-25%. The fifth? They’re lucky to get 10%. That’s why many small companies can’t survive. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of active generic drug manufacturers dropped from 142 to 97. The market is consolidating. The survivors aren’t the ones who entered first-they’re the ones who can produce at scale and survive on razor-thin margins.

Authorized Generics and Patent Settlements: The Hidden Rules

Brands aren’t just sitting back. They’re playing chess. One of their best moves? Launching an authorized generic during the first generic’s exclusivity period. About 65% of brand companies do this for high-value drugs. It’s legal. It’s smart. And it’s devastating for the first generic. Then there are patent settlements. In 2022, there were 147 agreements between brand and generic companies to delay entry. In the Humira biosimilar market, six companies agreed to stagger their entry between 2023 and 2025. That’s not competition-it’s collusion. The brand gets to keep revenue longer. The generics get a guaranteed slice of the market. Patients? They pay more for longer. The CREATES Act of 2020 helped by forcing brand companies to provide drug samples to generics. Before, some brands would refuse to sell samples, blocking generic development for years. Now, the average wait time dropped from 18.7 months to 4.3 months. But brand companies still file citizen petitions with the FDA-1,247 between 2018 and 2022-to delay approval of subsequent generics. Each petition adds 8.3 months to the timeline. It’s not about safety. It’s about buying time.Therapeutic Categories Don’t Play by the Same Rules

Not all generics are created equal. Cardiovascular drugs like statins? Once five generics enter, prices hit 12-15% of the brand. But oncology drugs? They stay at 35-40%. Why? Because they’re complex. They need special handling, cold storage, and trained staff. Fewer companies can make them. And they cost more to produce. CNS drugs like antidepressants and antipsychotics hover around 20-25% of brand price. They’re easier to make than cancer drugs, but harder than blood pressure pills. That’s why you’ll see 10+ competitors for metformin, but only 2-3 for insulin analogs. Biosimilars are a whole different beast. They’re biologic drugs-made from living cells, not chemicals. Developing one costs $100-250 million. So even with four competitors, prices only drop to 50-55% of the brand. That’s why biosimilar markets stay small. And why they’re the next big battleground.

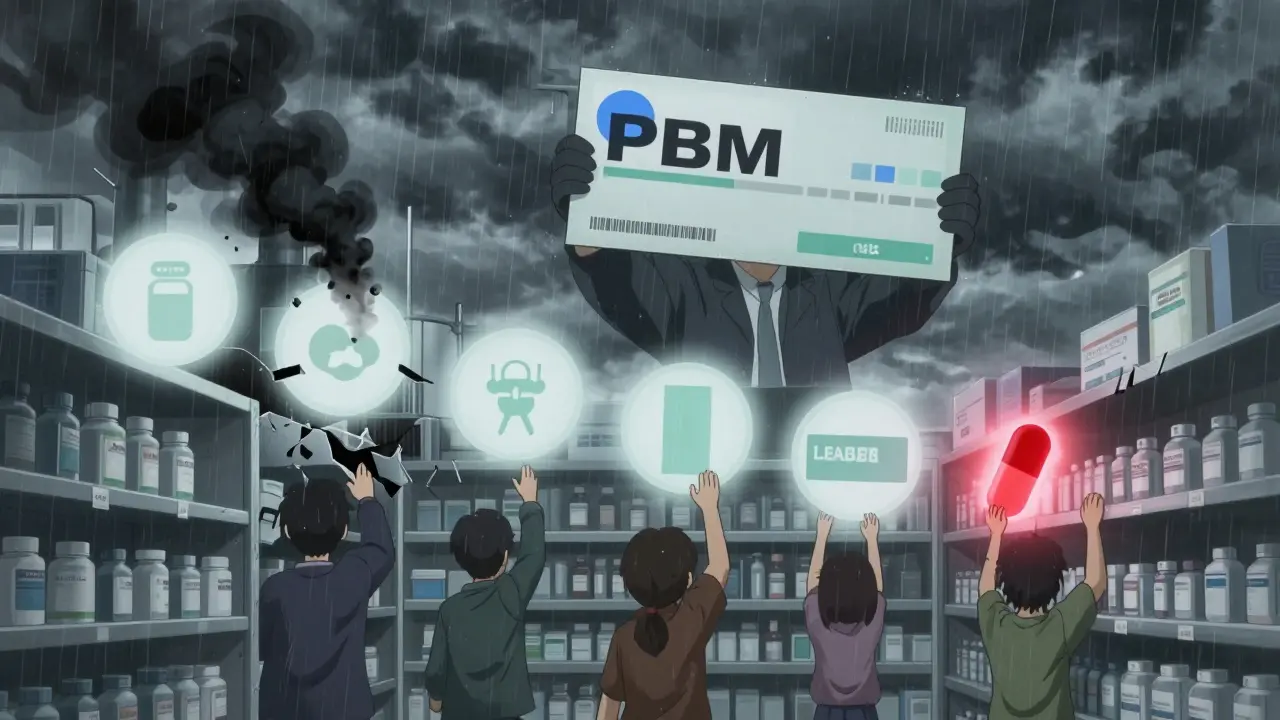

The Real Winner? The Pharmacy Benefit Manager

Who makes the most money in this system? Not the brand. Not the first generic. Not even the manufacturer. It’s the PBM. They negotiate rebates from every generic maker. The lower the price, the bigger the rebate. They pocket the difference. And they control which drugs get covered. A generic might be FDA-approved, but if the PBM doesn’t list it, patients can’t get it. That’s why the first generic to sign a PBM contract often captures 80-90% of the market-even if they weren’t the first to get FDA approval. This creates a perverse incentive: companies race not to be first to market, but first to sign a deal with CVS, UnitedHealth, or Express Scripts. The FDA approves. But the PBM decides who wins.What’s Next? The Market Is Changing

Experts are warning the system is breaking. Too many companies chasing too little profit. Too many shortages. Too many players exiting. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim at Harvard says the current model creates "perverse incentives"-too many generics enter simple drugs, leading to unsustainable price drops and supply crashes. Some propose market-based fixes: restricted entry for low-value generics, long-term contracts to stabilize supply, or even price floors. Others say the answer is more competition. But the data shows that after five competitors, prices don’t drop much further. The real problem isn’t too few generics-it’s too many chasing the same tiny slice of profit. By 2027, 70% of simple generic markets will have five or more competitors. Prices will be 10-15% of brand levels. But complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, and transdermal patches-will stay at 2-3 competitors with prices at 30-40%. That’s where the money is. And that’s where the next wave of innovation will happen.What is the 180-day exclusivity period for generic drugs?

The 180-day exclusivity period is a legal incentive under the Hatch-Waxman Act that rewards the first generic drug manufacturer to successfully challenge a brand-name drug’s patent. During this time, no other generic can legally enter the market. The first generic can charge higher prices and capture 70-80% of the market share, allowing them to recover litigation costs that often range from $5 million to $10 million.

How do authorized generics affect the first generic’s market share?

Authorized generics are versions of the brand-name drug produced by the original manufacturer and sold under a different label. When launched during the first generic’s exclusivity period, they immediately capture 20-40% of the market. This cuts the first generic’s market share from 70-80% down to 40-50%, reducing their revenue by 30-40%. Merck’s launch of an authorized generic for Januvia in 2019 is a well-documented example.

Why do generic drug prices drop so sharply after multiple entrants?

Each additional generic competitor drives prices down by 10-15% on average. The steepest drop occurs between the second and third entrants. By the time five or more generics are on the market, prices stabilize at about 17% of the original brand price. This is driven by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) using winner-take-all contracting, where the lowest bidder gets 100% of formulary placement, forcing companies to undercut each other.

Why are there shortages in generic drug markets with multiple competitors?

Despite having many manufacturers, 62% of generic drug shortages occur in markets with three or more competitors. This is because most companies rely on the same few contract manufacturing organizations (CMOs). When one CMO has a quality issue-like contamination or failed inspections-all drugs made there are recalled. Low profit margins also make it hard for companies to maintain inventory or invest in backup production lines.

Do patent settlements delay generic competition?

Yes. In 2022, there were 147 patent settlement agreements between brand and generic companies, with 65% including staggered entry dates to prevent market saturation. For example, in the Humira biosimilar market, six companies agreed to enter the market between 2023 and 2025. These deals delay competition and keep prices higher for longer, even though they’re technically legal under current law.

How do PBMs influence which generic drugs succeed?

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) control which drugs are covered by insurance plans. They use "winner-take-all" contracts, awarding 100% formulary placement to the lowest bidder. This means the first generic to sign a deal with a major PBM-like CVS Caremark or UnitedHealth’s Optum-can capture 80-90% of the market, even if they weren’t the first to get FDA approval. PBMs profit from rebates, so they push for the lowest possible price, regardless of supply stability.

Why do complex generics have fewer competitors than simple ones?

Complex generics-like inhalers, injectables, and transdermal patches-require advanced manufacturing, specialized equipment, and stricter quality controls. Development costs can be 5-10 times higher than for simple oral pills. As a result, only a few companies have the capability to make them. That’s why complex generics often have only 2-3 competitors, with prices staying at 30-40% of the brand price, compared to 10-15% for simple generics with five or more competitors.

Comments

Doug Gray

The whole system is just a rigged casino where PBMs hold the deck and patients lose every hand. 😒

They don’t care if you can’t get your meds-they just want the biggest rebate slice.

It’s not capitalism. It’s feudalism with spreadsheets.

And don’t get me started on how the FDA’s approval is just a ceremonial rubber stamp.

Real power? It’s in the PBM contracts. No one talks about that.

Meanwhile, we’re all just collateral damage in a game where the house always wins.

And yeah, I know I sound like a broken record-but it’s because the system never changes.

180-day exclusivity? More like 180 days of corporate theater.

Meanwhile, actual patients are rationing pills because the ‘cheapest’ option just got pulled for ‘quality issues.’

It’s not a market. It’s a performance art piece called ‘How to Profit from Suffering.’

Kristie Horst

It is, indeed, a profoundly concerning structural failure-particularly when one considers that the foundational premise of generic drug accessibility is predicated upon the notion of equitable, competitive pricing.

Yet, in practice, the incentives are inverted: profitability is derived not from therapeutic value, but from contractual leverage and regulatory arbitrage.

The PBM model, in its current form, functions less as a steward of patient care and more as a rent-seeking intermediary.

One cannot help but wonder: if the goal is to reduce cost and increase access, why is the system structured to reward the lowest bid rather than the most reliable supplier?

And while the CREATES Act was a step in the right direction, it remains a Band-Aid on an arterial bleed.

It is not merely a market inefficiency-it is a moral failure disguised as economic policy.

Perhaps we ought to consider public procurement models, as seen in Canada or the UK, where negotiation is transparent and supply is stabilized.

But then again, who benefits from transparency? Not the current players.

It is, as they say, easier to change the rules than to change the players.

Laia Freeman

OMG I JUST REALIZED-PBMs are basically the middlemen who make money off everyone losing?? 😱

Like, you think you’re saving money with generics but NOPE the PBM is laughing all the way to the bank with their 40% rebate!!

And then the drug disappears because some factory in India had mold?? 🤯

Why are we letting this happen??

My grandma’s blood pressure med vanished for 3 months last year-she had to go to 3 pharmacies before finding it.

And the brand? Still charging $300 for the same damn pill.

Someone needs to burn this whole system down.

Also-why do we even have PBMs?? Can’t insurers just negotiate directly??

It’s like having 7 middlemen between you and your pizza delivery guy.

WE NEED REFORM. NOW. 🙏

Keith Oliver

Let’s be real-the entire generic drug ecosystem is a textbook case of regulatory capture. The Hatch-Waxman Act was never meant to be weaponized into a profit-maximizing oligopoly.

First generic gets exclusivity? That’s not competition-it’s a cartel license.

And authorized generics? That’s not market efficiency-that’s brand companies playing both sides of the board.

And let’s not pretend PBMs are neutral actors. They’re private equity-backed monopolists who control access through opaque rebate structures.

Even the FDA’s approval process is gamed: citizen petitions are just litigation-by-proxy.

Meanwhile, the real innovators? The ones who could make biosimilars viable? They’re priced out before they even start.

It’s not a free market. It’s a controlled demolition of public health.

And you know what’s worse? Everyone who works in pharma knows this. And they’re still getting bonuses.

The only thing that’s ‘generic’ here is the corruption.

Kacey Yates

Stop acting like this is about competition. It’s about who can survive on 5% margins.

Third-party manufacturers? They’re all in China and India.

One FDA inspection failure = 10 brands out of stock.

And the PBM doesn’t care-they just switch to the next lowest bidder.

It’s a race to the bottom and we’re all falling.

Also-why are we still using paper forms for drug approvals in 2025?

Fix the system or shut it down.

Patients are dying because of bureaucracy.

That’s not a policy debate. That’s a crime.

ryan Sifontes

They’re all in on it.

Big Pharma, PBMs, FDA, Congress.

They’re not just letting this happen-they designed it.

Why do you think the same 3 factories make 80% of our pills?

Because they’re owned by the same conglomerates that own the brands.

Authorized generics? Just a smokescreen.

And those patent settlements? Collusion with a lawyer’s signature.

They want shortages.

Because when you can’t get your meds, you go back to the brand.

And the brand charges $300 again.

It’s not a market failure.

It’s a profit plan.

Laura Arnal

Thank you for writing this-it’s so important and so rarely explained clearly 💙

It’s heartbreaking to see how the system meant to help people ends up hurting them.

But I’m hopeful! There are advocates pushing for public option generics and state-level purchasing pools.

And more people are waking up to how PBMs work.

Change is slow, but it’s happening.

Keep sharing this stuff-it’s lighting fires in the right places 🔥

Also, if you’re a patient struggling to get meds, DM me-I know some resources that can help.

Jasneet Minhas

As someone from India, where we produce nearly 40% of the world’s generics, I find this both fascinating and alarming.

Our factories supply the U.S. market, yet we lack the regulatory infrastructure to ensure consistent quality.

Meanwhile, American PBMs demand prices so low that manufacturers cut corners.

It’s a global supply chain with no global accountability.

And yet-when a recall happens, the blame falls on ‘foreign manufacturing.’

But who set the price ceiling that forced the cut corners?

It’s not the factory owner.

It’s the PBM in Minneapolis.

And the system? It’s designed to make us look away.

Eli In

This is one of those topics that feels so complex, but really, it’s just about power.

Who gets to decide what’s affordable?

Who gets to decide who lives or dies because of a $2 pill?

It’s not about science.

It’s not even about economics.

It’s about who controls the flow of life-saving medicine.

And right now? That control is in the hands of people who don’t take the pills.

Maybe the real solution isn’t more competition.

Maybe it’s rethinking who gets to be in charge.

Just food for thought 🌍❤️