When a brand-name drug company protects its product with a patent, it gets a monopoly. That’s how they recoup the cost of research. But the 30-month stay is the legal pause button that stops generic drugs from hitting the market-even when the FDA says they’re safe and ready. This isn’t a glitch. It’s a rule built into U.S. drug law. And it’s costing consumers billions every year.

What Exactly Is the 30-Month Stay?

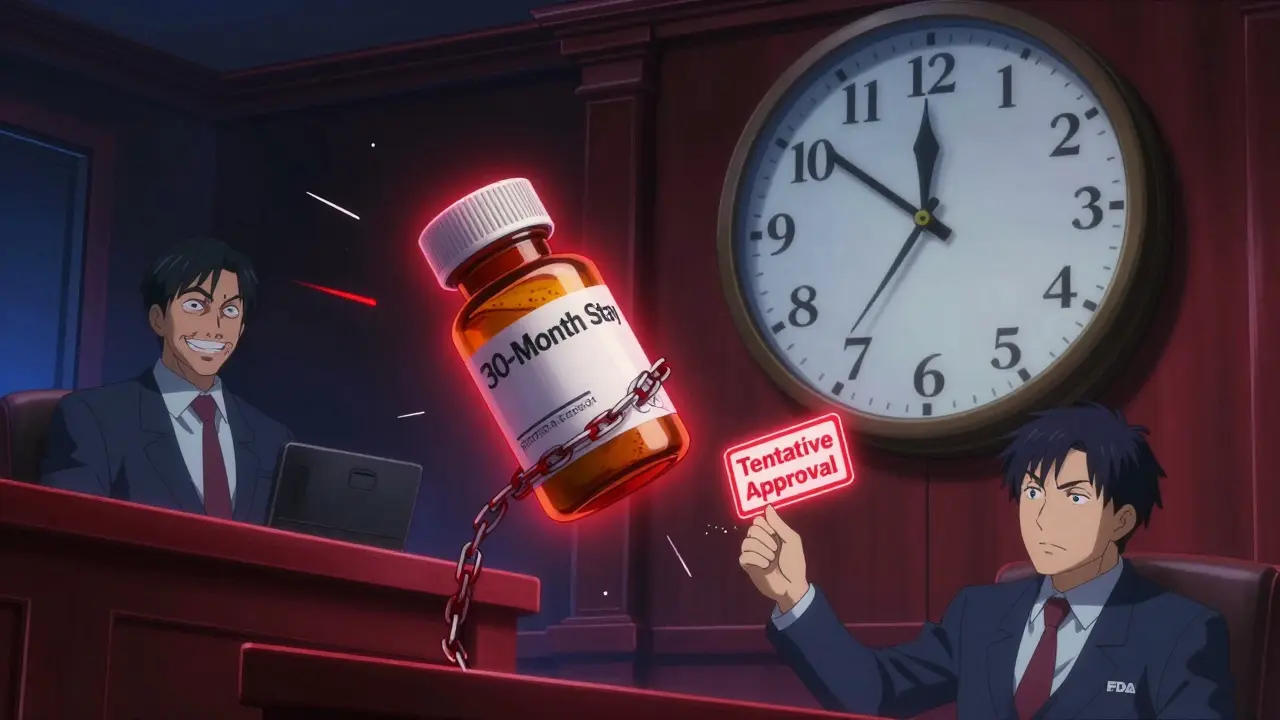

The 30-month stay is part of the Hatch-Waxman Act, passed in 1984. It was meant to strike a balance: let generic companies challenge weak patents, but give brand companies time to defend them in court. Here’s how it works in practice.When a generic manufacturer files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), they must declare whether they’re challenging any patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. If they say yes-that’s called a Paragraph IV certification-they have to notify the brand company. If the brand company sues for patent infringement within 45 days, the FDA is legally blocked from approving the generic for up to 30 months.

That’s it. No judge needs to rule. No proof of harm needed. Just a lawsuit triggers the hold. And the FDA can’t approve the drug during that time-even if the generic passes all safety and quality checks. The clock starts ticking the day the last patent holder gets the notice.

Why Does This Delay Generic Drugs So Long?

The 30-month stay doesn’t just delay approval. It delays access. And it’s not always about real patent disputes.Brand companies often list dozens of patents on a single drug. Some are core patents-covering the actual molecule. Others are secondary: a new tablet coating, a slightly different dose, a packaging method. A 2019 Brookings study found that 67% of patents listed in the Orange Book for top-selling drugs were filed after the original drug got approved. These aren’t innovations-they’re legal maneuvers.

Even though the 2003 Medicare law stopped companies from triggering multiple 30-month stays for the same generic, they still use other tactics. They file new lawsuits after the first one ends. They extend patents with minor changes. They sue over patents that are clearly invalid. The system doesn’t punish this behavior-it rewards it.

According to FTC data from 2021, 78% of Paragraph IV patent lawsuits end in settlements that delay generic entry beyond the patent’s original expiration date. That’s not litigation. That’s pay-for-delay.

Tentative Approval Isn’t the Same as Approval

You might hear that the FDA gives “tentative approval” during the 30-month stay. That sounds like progress. But it’s not.Tentative approval means the FDA has reviewed the data and says, “This drug meets our standards.” But they can’t let it hit shelves until the stay ends or the court rules. In 2022, the FDA gave tentative approval to 78% of ANDAs still in litigation. That’s 816 applications sitting on the shelf, ready to go, but legally frozen.

And here’s the kicker: even after the stay expires, most generics don’t launch right away. FDA data shows a median gap of 3.2 years between stay expiration and actual market entry. Why? Because brand companies often sign deals with the first generic challenger to delay launch. Or the generic maker isn’t ready to scale production. Or they’re waiting for the 180-day exclusivity window to start.

Who Pays the Price?

The U.S. generic drug market is huge: $127.4 billion in 2022. It fills 90% of prescriptions. But it only accounts for 23% of total drug spending. That’s because brand drugs still cost 10 to 20 times more.When a generic enters, prices drop 80-85% within a year. But the 30-month stay keeps those savings locked up. The FTC estimates that patent litigation delays tied to the stay add $13.9 billion to U.S. drug costs every year. That’s money families pay out of pocket. That’s money Medicare and Medicaid spend.

And it’s not just about money. People with chronic conditions-diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma-can’t wait. They need affordable meds now. But the system is designed to make them wait.

How Other Countries Handle It

The U.S. is an outlier. In Europe, there’s no 30-month stay. Generic companies can file for approval as soon as the patent expires. If a brand company sues, the court handles it-but the generic can still launch unless a judge issues a specific injunction.Canada has a 24-month stay, shorter than the U.S. version. And they don’t allow patent thickets the same way. Australia and the U.K. have similar systems: no automatic regulatory hold based on litigation.

The U.S. system isn’t about protecting innovation. It’s about controlling timing. And that timing is manipulated to maximize profits.

What’s Changing?

There’s growing pressure to fix this. In 2023, Congress introduced the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act. It would cut the 30-month stay to 18 months and ban stays for secondary patents.The FTC has been pushing for years. Their 2022 report showed that brand companies now list an average of 8.3 patents per drug in the Orange Book-up from just 1.2 in 1995. That’s not innovation. That’s obstruction.

The FDA also proposed new rules in 2023 requiring more detailed patent disclosures. That could help courts and generic companies spot weak patents faster.

But change moves slowly. Brand drug companies spent over $100 million lobbying on this issue in 2022 alone. They argue that without the stay, they’d stop investing in new drugs. But the numbers don’t back that up. Since 1984, over 14,000 generics have been approved. And brand companies still made $2.2 trillion in savings for consumers-while maintaining massive profits.

What’s Next for Generic Manufacturers?

For generic companies, the 30-month stay isn’t just a legal hurdle-it’s a financial one. A 2022 survey found that 63% of generic manufacturers spend $3-5 million per ANDA on patent litigation. That’s money that could go toward research, quality control, or lowering prices.Many now have full-time Hatch-Waxman teams. They hire lawyers who charge $1,800 an hour. They track every patent, every filing, every court date. It’s a full-time job just to get a drug approved.

But there’s a silver lining: competition works. When multiple generic companies challenge the same drug, approval comes faster. In 2022, drugs with multiple Paragraph IV filers reached the market 8.2 months sooner than those with just one challenger.

That’s why companies like Teva, Sandoz, and Sun Pharma are racing to be first. The first one gets 180 days of exclusivity. That’s a huge incentive. But it also creates a race to the bottom-where the first challenger might agree to delay launch in exchange for a cut of the profits.

Final Reality Check

The 30-month stay sounds like a technical legal detail. But it’s the reason millions of Americans pay more for their meds than they should. It’s not broken-it’s working exactly as designed. For brand companies.The system was supposed to balance innovation and access. Instead, it’s become a tool to extend monopolies. And while the FDA approves generics, the courts and the law keep them off the shelves.

Real reform won’t come from better paperwork. It will come from changing the rules. Cut the stay. Ban patent thickets. End pay-for-delay deals. Until then, the 30-month stay remains one of the biggest hidden barriers to affordable medicine in the U.S.

What triggers the 30-month stay in generic drug approval?

The 30-month stay is triggered when a generic drug manufacturer files a Paragraph IV certification challenging a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book, and the brand-name drug company files a patent infringement lawsuit within 45 days of receiving notice. Once the lawsuit is filed, the FDA is legally barred from approving the generic for up to 30 months.

Can the FDA approve a generic drug during the 30-month stay?

No, the FDA cannot grant final approval during the 30-month stay. However, it can issue tentative approval if the application meets all safety, efficacy, and manufacturing standards. Tentative approval means the drug is ready to launch as soon as the stay ends or the court rules in favor of the generic.

Does the 30-month stay always last 30 months?

Not always. The stay ends early if the court rules in favor of the generic company, if the patent is found invalid or not infringed, or if the brand company drops the lawsuit. The stay can also be extended beyond 30 months if litigation isn’t resolved, though this is rare. Courts can shorten it if they determine the lawsuit was filed in bad faith.

Why do generic drugs still take years to launch after the 30-month stay ends?

Even after the stay ends, many generics don’t launch immediately. Brand companies often strike pay-for-delay deals with the first generic challenger, paying them to postpone entry. Other reasons include production delays, supply chain issues, or waiting for the 180-day exclusivity period to begin. The median gap between stay expiration and launch is 3.2 years.

Are there efforts to change the 30-month stay rule?

Yes. In 2023, Congress introduced the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, which proposes reducing the stay to 18 months and banning it for secondary patents. The FTC and FDA have also pushed for reforms to limit patent thickets and improve transparency in the Orange Book. Many experts believe major changes are likely within the next five years.

Comments

John Ross

The 30-month stay is a legal loophole dressed up as policy-brand pharma doesn’t innovate, they litigate. They file patents on fucking packaging colors and then cry foul when generics try to compete. This isn’t capitalism, it’s rent-seeking with a white coat.

FTC data shows 78% of these lawsuits end in pay-for-delay settlements. That’s collusion with a subpoena. And the FDA? They’re just the janitor cleaning up after the party.

Meanwhile, diabetics in Ohio are choosing between insulin and groceries because a CEO in New Jersey got a 30-month extension on a patent for a 1980s molecule. Wake up.

Brendan F. Cochran

so like… why dont we just sue the drug companies into oblivion? i mean, theyre literally holding medicine hostage. its not even a secret. theyre not inventing anything, theyre just gaming the system. and congress? theyre getting paid to look away. #endhatchwaxmanabuse

Roshan Aryal

Let me tell you something about American exceptionalism in pharma-this 30-month stay isn’t protection, it’s performance art. In India, generics hit the market the day patents expire. In Germany, courts move fast. Here? We turn pharmaceuticals into a poker game where the house always wins because the house writes the rules.

You call it innovation? I call it legalized theft with a FDA stamp.

Stephen Craig

The system works exactly as intended-for profit, not patients.

Charlotte N

i keep hearing "tentative approval" but like… what does that even mean if you can't sell it? it's like getting your driver's license but being told you can't drive for two and a half years because someone else is suing your car

Jennifer Glass

I used to work in pharmacy. I’ve seen people cry because they couldn’t afford their blood pressure med. And then I’d look up the patent status-yep, 30-month stay. It’s not complicated. It’s cruel. And it’s not about innovation. It’s about who gets to profit from sickness.

There’s a woman in my neighborhood who skips doses so her kid can eat. That’s the human cost of a legal technicality.

melissa cucic

It’s fascinating how the Hatch-Waxman Act was sold as a compromise-but over time, it became a weapon. The original intent was to balance innovation and access. Now? It’s a monopoly extension machine. The Orange Book is a graveyard of trivial patents-coatings, shapes, delivery mechanisms. None of it changes efficacy. All of it delays generics.

The FTC’s numbers are damning: 8.3 patents per drug on average now, up from 1.2 in 1995. That’s not innovation. That’s obstruction. And the fact that Congress hasn’t fixed it, despite knowing this for decades, speaks volumes.

And yet, we still pretend this is a free market. It’s not. It’s a cartel with a FDA seal.

Real reform would ban stays for secondary patents, cap litigation costs for generics, and require public disclosure of pay-for-delay deals. But lobbyists spend $100 million a year to stop that. Who are we really serving?

Jacob Milano

My dad’s on insulin. He’s 72. He pays $400 a month. The generic? $20. But it’s been stuck in litigation for 28 months. He’s not mad-he’s just tired. He doesn’t know the legal terms. He just knows he’s choosing between his meds and his grandkid’s birthday present.

This isn’t policy. It’s personal. And it’s happening to millions.

People talk about "market forces" like it’s magic. But here? The market is rigged. And the people paying are the ones who can least afford it.

Jack Wernet

While the systemic issues are deeply concerning, I must note that the 30-month stay was designed to prevent frivolous litigation from derailing legitimate patent protections. Without it, brand companies might be disincentivized from investing in novel therapies.

That said, the abuse of secondary patents and the rise of pay-for-delay agreements are clear signs that the system has been corrupted. The solution isn’t to eliminate the stay entirely-it’s to reform its application. Narrowing it to core patents, increasing transparency in the Orange Book, and penalizing bad-faith litigation would preserve innovation while restoring access.

We can do better without dismantling the entire framework.

Oluwapelumi Yakubu

Bro, this ain’t even America’s problem-it’s capitalism’s problem. In Nigeria, we don’t have this mess. If the patent’s dead, the generic’s on the shelf. No court drama. No lobbying. Just people getting medicine. You think this is about health? Nah. It’s about who owns the right to profit from pain.

They patent the color of the pill. The shape. The fucking wrapper. And you call that innovation? That’s a scam with a PhD.

Meanwhile, in Lagos, a man buys his HIV meds for $2. Here? $800. And you wonder why the world hates us?

mark etang

As a policy analyst with over two decades of experience in pharmaceutical regulation, I must emphasize that the 30-month stay, while imperfect, serves a critical function in preserving intellectual property rights that incentivize R&D investment. The pharmaceutical industry spends an average of $2.6 billion and 10–15 years to bring a single drug to market. Without robust legal protections, innovation would collapse.

That said, the proliferation of secondary patents-particularly those filed post-approval-represents a significant regulatory failure. The FDA and Congress must act decisively to restrict Orange Book listings to only those patents that claim the active pharmaceutical ingredient or a novel, non-obvious formulation with clinical benefit.

Furthermore, the FTC’s findings on pay-for-delay agreements warrant immediate antitrust enforcement. Settlements that delay generic entry beyond patent expiration constitute a per se violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Reform is not only necessary-it is overdue. However, we must ensure that any legislative change does not inadvertently undermine the foundational incentive structure that has enabled breakthroughs in oncology, rare diseases, and immunotherapy over the past four decades.

The goal should be precision, not destruction.

Terri Gladden

wait so if the FDA says its safe but the court says no then like… who even is in charge here?? i feel like the system is just broken on purpose??

also why do i keep seeing the same drug companies in every lawsuit?? its like theyre all friends??

Joseph Snow

Let me guess-this is part of the globalist deep state’s plan to collapse American healthcare so they can replace it with WHO-controlled biometric ID pills. The 30-month stay? A distraction. The real agenda is population control through controlled access to medication. Check the FDA’s funding sources. Check the patent attorneys’ political donations. This isn’t about profit-it’s about power.

And don’t you dare say this is about patients. Patients are pawns. The real players are the ones who own the courts, the FDA, and the media.

Ethan Purser

you ever notice how every time someone tries to fix this, the same 5 pharma CEOs show up on C-SPAN saying "we need to protect innovation"? like, bro, your drug was invented in 1998. you’re not innovating. you’re just holding a patent hostage like a toddler with a cookie.

and the worst part? they’re not even hiding it. they’re proud of it. they have PowerPoint slides on how to extend monopolies. this isn’t capitalism. this is feudalism with a better PR team.

and the FDA? they’re just the guy who keeps saying "we approve it!" while the court says "nope, wait 30 more months."

we’re not just paying more-we’re paying for the illusion that this system works.

the only thing more tragic than the cost? the fact that no one in power gives a damn.

Jennifer Glass

It’s wild how the system rewards delay. The first generic to file gets 180 days of exclusivity-but then they often agree to delay launch anyway. So the brand company pays them to not compete. That’s not market competition. That’s collusion with a profit split.

And we wonder why drug prices are so high.