Most people think of loperamide as just another medicine for upset stomachs. You grab a bottle of Imodium A-D at the grocery store, pop a couple pills when you’re rushing to the bathroom, and move on. But what if that little blue bottle could quietly kill you? That’s not fear-mongering-it’s fact. Since 2010, loperamide abuse has surged, tied directly to the opioid crisis. People aren’t using it for diarrhea anymore. They’re swallowing dozens of pills a day to fight opioid withdrawal, chasing a faint high, and putting their hearts at serious risk.

How Loperamide Works-And Why It’s Being Misused

Loperamide was designed to be safe. Unlike older opioid-based diarrhea drugs, it was meant to work only in the gut, not the brain. At normal doses-2 to 4 mg-it binds to opioid receptors in the intestines, slowing down bowel movements without causing drowsiness or euphoria. That’s because a natural pump in your body, called P-glycoprotein, blocks it from crossing into the brain.

But when someone takes 50, 100, even 400 mg a day-sometimes by swallowing 20 or 30 pills at once-that pump gets overwhelmed. Suddenly, loperamide slips through, reaches the brain, and starts acting like an opioid. Not a strong one. Not like heroin or oxycodone. But enough to dull withdrawal symptoms: sweating, shaking, nausea, anxiety. For someone trying to quit opioids without medical help, that’s tempting.

And it’s easy to get. No prescription. No doctor’s note. Just a quick trip to the pharmacy-or a click online. Between 2011 and 2014, abuse cases jumped 71%. By 2017, there were over 5,000 emergency reports of loperamide exposure in the U.S. alone.

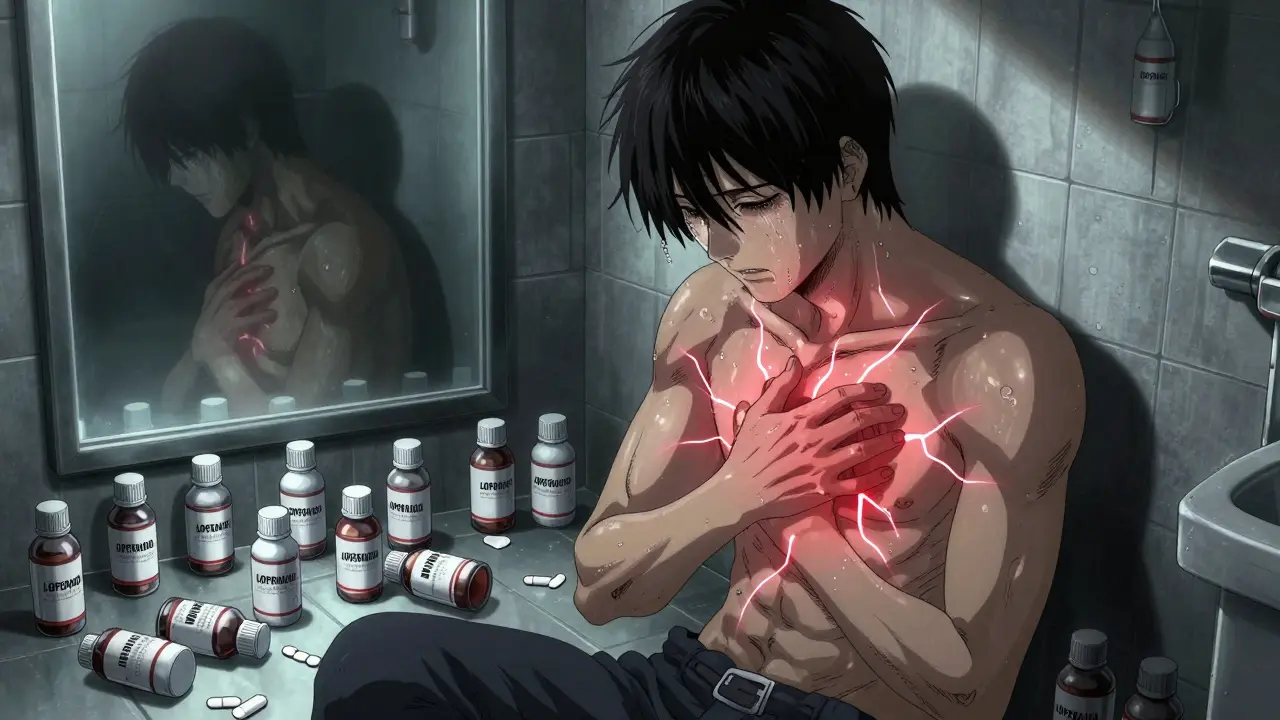

The Silent Killer: Heart Damage from High Doses

Here’s the catch: loperamide doesn’t just mess with your gut or brain. It messes with your heart. At abusive doses, it blocks critical electrical channels in heart muscle cells-specifically the hERG potassium channel and sodium channels. This causes your heart’s rhythm to go haywire.

The result? QT interval prolongation. QRS widening. Torsades de Pointes. These aren’t medical buzzwords. They’re life-threatening arrhythmias. Your heart skips, stutters, or stops. Some people collapse. Others die suddenly, with no warning.

The FDA reviewed 48 serious cardiac events linked to loperamide. More than half happened after 2010. In one case, a 32-year-old man took 80 mg a day (20 times the max recommended dose) to manage opioid withdrawal. He ended up in the ER with polymorphic ventricular tachycardia-a chaotic, deadly heart rhythm. His QTc was over 500 ms. Normal is under 450.

And here’s what makes it worse: standard drug tests don’t detect loperamide. ER doctors often miss it. They see chest pain, fainting, or cardiac arrest-and assume it’s a heart attack, not a drug overdose. Delayed diagnosis means delayed treatment. And in these cases, every minute counts.

Warning Signs You Can’t Ignore

If someone you know is using loperamide beyond the label-especially if they have a history of opioid use-watch for these red flags:

- Taking more than 8 mg per day (the OTC max), often 50 mg or higher

- Buying multiple bottles at once, or ordering large quantities online

- Using loperamide with other drugs like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), cimetidine (Tagamet), or quinidine to boost its brain effects

- Complaints of chest pain, fluttering heartbeat, dizziness, or fainting spells

- Sudden constipation, bloating, or vomiting-signs the gut is shutting down

- Withdrawal symptoms returning quickly after stopping loperamide, leading to higher doses

Reddit threads from opioid recovery communities are full of these stories. One user wrote: “Tried 50 mg Imodium to help with withdrawal… wound up in ER with chest pains.” Another: “I took 120 mg over two days. I thought I was fine. Then my heart started racing like crazy.”

These aren’t outliers. They’re warnings.

Why People Turn to Loperamide-And Why It’s a Trap

People don’t abuse loperamide because they’re reckless. They do it because they’re desperate.

Opioid withdrawal is brutal. It feels like the flu, amplified by terror. Many can’t access or afford buprenorphine or methadone. Some fear stigma. Others don’t know where to turn. Loperamide is there-cheap, legal, and easy. It’s the only tool they have.

But here’s the cruel twist: loperamide doesn’t work well for opioid withdrawal. It doesn’t produce strong euphoria. So users keep increasing the dose, chasing something that never fully comes. And with each extra pill, they inch closer to cardiac arrest.

Unlike methadone or buprenorphine-which are dosed carefully under medical supervision-loperamide has no safety net. No monitoring. No antidote for the heart damage. Naloxone can reverse opioid effects in the brain, but it won’t fix a prolonged QT interval. That requires magnesium, pacing, and ICU care.

What’s Being Done-and What’s Still Missing

The FDA didn’t pull loperamide off shelves. They added stronger warnings to packaging in 2016. The industry responded by limiting packages to 45 mg or less per unit in 2019. Some pharmacies now keep it behind the counter. Sales dropped 12% between 2016 and 2020.

But abuse didn’t stop. It just moved. People now buy bulk bottles online, often from overseas sellers. They use apps, dark web markets, or even Facebook groups to find suppliers. The 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found 580,000 Americans used loperamide non-medically in the past year. Among people with opioid use disorder, nearly 1 in 6 reported doing it.

And the deaths? Between 2011 and 2020, 17 confirmed deaths were directly tied to loperamide toxicity. The real number is likely higher. Many are buried under “cardiac arrest” or “sudden death” on death certificates.

What to Do If You or Someone You Know Is Using Loperamide Abusively

If someone is taking more than 8 mg a day to manage withdrawal or get high, they need help-not judgment.

- Stop loperamide immediately. Abruptly quitting can worsen withdrawal, but continuing is deadly.

- Seek emergency care if there’s chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, or fainting. Tell the ER team you suspect loperamide overdose.

- Ask for an ECG. A prolonged QTc is the clearest sign of toxicity.

- Call SAMHSA’s National Helpline: 1-800-662-HELP. They connect people to free or low-cost treatment for opioid use disorder.

- Encourage treatment with buprenorphine or methadone. These are proven, safe, and supervised.

Family doctors, pharmacists, and friends play a role too. If you see someone buying 10 bottles of Imodium in a month, ask. Don’t assume they’re just “having bad digestion.” Say: “I’m worried about you. Have you been using this for something else?”

The Bottom Line

Loperamide isn’t a safe substitute for opioid treatment. It’s a dangerous gamble with your heart. The same pill that helps with a bad taco can kill you if you take too many. And the people most at risk? They’re not addicts looking for a high. They’re people trying to survive withdrawal-with no other options.

That’s why awareness matters. That’s why labeling matters. That’s why we need better access to real treatment-not more pills on the shelf.

If you’re using loperamide to cope with opioid withdrawal, you’re not alone. But you don’t have to do it alone. Help exists. And it’s safer than any bottle of Imodium.

Can you overdose on loperamide even if you’re not trying to get high?

Yes. Even people taking loperamide for diarrhea can overdose if they exceed the recommended dose-especially if they’re taking it multiple times a day or combining it with other drugs that block its metabolism, like cimetidine or quinidine. The maximum daily OTC dose is 8 mg. Taking more than that, even for legitimate reasons, increases the risk of heart rhythm problems. Some people accidentally overdose because they don’t realize how quickly the dose adds up.

Is loperamide addictive like other opioids?

Loperamide doesn’t produce strong euphoria, so it’s not addictive in the classic sense. But it can lead to physical dependence. People who use it heavily for weeks or months to manage opioid withdrawal may experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop-like anxiety, sweating, nausea, and muscle aches. This drives them to keep taking it, creating a cycle of misuse. It’s not about the high; it’s about avoiding the pain of withdrawal.

Why doesn’t the FDA ban loperamide if it’s so dangerous?

The FDA keeps loperamide available over-the-counter because it’s extremely effective and safe when used as directed-for treating acute diarrhea. Millions of people benefit from it every year. Banning it would hurt public health by removing a convenient, low-cost treatment. Instead, regulators focus on education, warning labels, and packaging limits to reduce abuse without taking away its medical value.

Can you test for loperamide in a standard drug screen?

No. Standard urine or blood drug tests don’t detect loperamide. It won’t show up on panels for opioids, benzodiazepines, or amphetamines. That’s why it’s often missed in emergency rooms. To confirm loperamide overdose, doctors need to order a specific toxicology test, which isn’t routinely done unless there’s a strong suspicion. This makes diagnosis harder and delays life-saving treatment.

What should you do if someone collapses after taking loperamide?

Call 911 immediately. Do not wait. If the person is unconscious or not breathing normally, start CPR if you’re trained. Tell emergency responders the person may have taken a large amount of loperamide. Hospitals can administer magnesium sulfate to stabilize heart rhythm, and they may use a pacemaker if needed. Time is critical-heart damage from loperamide can progress rapidly.

Are there safer alternatives to loperamide for opioid withdrawal?

Yes. Medications like buprenorphine and methadone are FDA-approved for treating opioid use disorder and are far safer than loperamide. They reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms without the risk of fatal heart rhythms. Naltrexone is another option for those who’ve already detoxed. These treatments require a prescription but are covered by most insurance and available through clinics. SAMHSA’s helpline (1-800-662-HELP) can connect you to local providers.

Comments

Bret Freeman

This is exactly why we need to stop treating addiction like a moral failing. People aren't doing this for fun. They're doing it because the system failed them. The pharmacy counter isn't a treatment center, and no amount of warning labels fixes that.

EMMANUEL EMEKAOGBOR

I appreciate the thoroughness of this post. In Nigeria, access to proper medical care for opioid dependence is nearly nonexistent. While loperamide abuse is not widespread here, the underlying issue-lack of affordable, stigma-free treatment-is universal. We must address the root cause, not just the symptom.

CHETAN MANDLECHA

I work in a pharmacy in India. We've seen people buy 20+ packs at once. No one asks questions. No one checks. It's not about enforcement-it's about awareness. If a customer says they need it for 'digestive issues' and buys 12 bottles, we should be trained to say something. Anything.

Jillian Angus

I know someone who did this. They didn't even know it could kill them. They just wanted to stop shaking. No one told them. No one asked. It's scary how easy it is to slip into something deadly without realizing it

Gray Dedoiko

I used to work ER. We had a guy come in last year-34, no history of heart issues. QT was 612. Turned out he was taking 150 mg a day to get through his dad's funeral. No one knew. No one suspected. He survived. But he needed a pacemaker now. This isn't theoretical.

Lu Jelonek

In my community, we don't talk about addiction. We whisper. We look away. But this isn't just about drugs-it's about dignity. People need care, not judgment. The fact that loperamide is still sold like candy while buprenorphine requires a specialist is a failure of policy, not character.

siddharth tiwari

Big Pharma knows this is happening. They dont care. Theyre making billions off the opioid crisis and now theyre letting people kill themselves with imodium because its not profitable enough to ban. The FDA is just a front for the drug companies. Watch what happens when they finally pull it off shelves

Adarsh Dubey

The data here is solid. The FDA's 2016 labeling update and 2019 packaging limits were reasonable steps, but they're insufficient. What's needed is a public health campaign that targets at-risk communities with clear, non-stigmatizing messaging-distributed through community centers, churches, and even Reddit threads like this one.

Bartholomew Henry Allen

America is weak. We let people die because we're too soft to control medicine. If you can't handle your withdrawal, you shouldn't be alive. Lock up the pills. Make it hard. Make it illegal. No more coddling addicts. This is a nation of losers who want everything handed to them

Andrea Di Candia

There's hope here. The fact that people are even talking about this means we're starting to see the humanity behind the addiction. I've met people who took loperamide to get through one more day so they could find a rehab bed. They didn't want to die. They just wanted to feel normal again. That's not a crime. That's a cry for help.

bharath vinay

They're lying about the numbers. 580k users? That's fake. The government inflates these stats to justify more funding for rehab centers. Real addicts don't use loperamide-they use fentanyl or heroin. This is just a distraction to make people think the opioid crisis is getting worse so they can push more surveillance tech and drug testing

Dan Gaytan

I lost my brother to this. He took 120 mg over three days. Thought he was fine. Then he just... stopped breathing. No signs. No warning. The coroner said 'cardiac arrest.' We didn't know until the toxicology report came back. Please, if you're reading this and you're doing this-stop. Talk to someone. You're not alone. 💔

Wilton Holliday

If you're reading this and you're using loperamide to get through withdrawal-you're not broken. You're just trying to survive. The fact that you're here means you're still fighting. That counts. Please, call SAMHSA. Even if you're scared. Even if you think no one will understand. Someone will. I promise. You don't have to do this alone.

Harsh Khandelwal

Loperamide? More like loper-kill. These dumbasses think they're smart taking 400 mg like it's a vitamin. Meanwhile their heart's doing the cha-cha and they're too high on denial to notice. The only thing worse than the overdose is the fact that their mom still buys them Imodium like it's candy. Wake up, people.

Andy Grace

I'm from Australia. We have stricter controls here. Loperamide is behind the counter, limited to 10 tablets per sale, and pharmacists are trained to ask questions. It's not perfect, but it's a start. The real issue isn't the drug-it's the lack of accessible mental health and addiction services. Fix that, and you fix the abuse.